The Heavy Burden of Proof in Research

In the world of research, we live by a few golden rules. Two of the most famous come from David Hume and Carl Sagan, and they set the tone for how we handle truth in the Western world.

David Hume (1748) famously said:

"A wise man apportions his beliefs to the evidence."

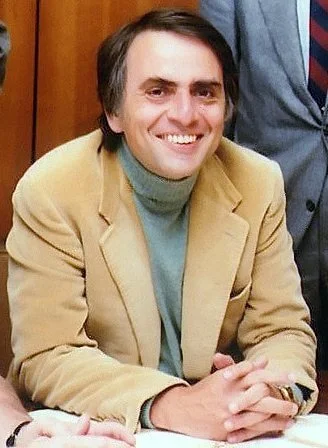

Carl Sagan later echoed this sentiment with his famous "Sagan Standard":

"Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence."

These quotes aren't just philosophical musings; they are the bedrock of quantitative research. But what do they actually mean for us as researchers and consumers of information?

The Mathematics of Belief

Hume’s quote reminds me of the fundamental nature of Western science: belief is a variable that scales with data.

In quantitative research, we don't just "believe" a hypothesis because it feels right. We use data as the evidence to support our claim. The more data we have (and the statistically stronger that data is), the more we are allowed to believe it. If the data isn't there, we don't just hope for the best; we go back to the drawing board.

The "Sagan Standard" in Psychology

Sagan’s quote takes it a step further. It implies that not all claims are created equal.

If I claim that "people get sad sometimes," I don't need much evidence; common experience supports it. But if I claim that "I can cure depression instantly with a wave of my hand," that is an extraordinary claim. To be taken seriously, I would need extraordinary, irrefutable evidence.

In our culture, this skepticism is a protective mechanism. It keeps us grounded. It forces us to prove our work.

The Problem: Who Defines "Evidence"?

However, as I reflect on these quotes, I also see the limitation. While I fully agree that evidence is necessary, a problem arises when we rigidly define what "evidence" looks like.

In the scientific community, "evidence" is often synonymous with numerical data or physical, observable phenomena. But what happens when we study the invisible? What happens in transpersonal psychology, where we explore consciousness, spirituality, and internal states?

Sometimes, valid human experiences are dismissed simply because they cannot be easily quantified into a chart or a P-value. The "extraordinary" nature of the human spirit often defies standard measurement.

Conclusion

These quotes speak volumes about how we conduct research. They challenge us to be rigorous and demanding of the truth. But they also invite us to ask a deeper question: Are we open to evidence that doesn't fit neatly into a spreadsheet?