The Turkey Problem: A Lesson in Trust, Betrayal, and Statistics

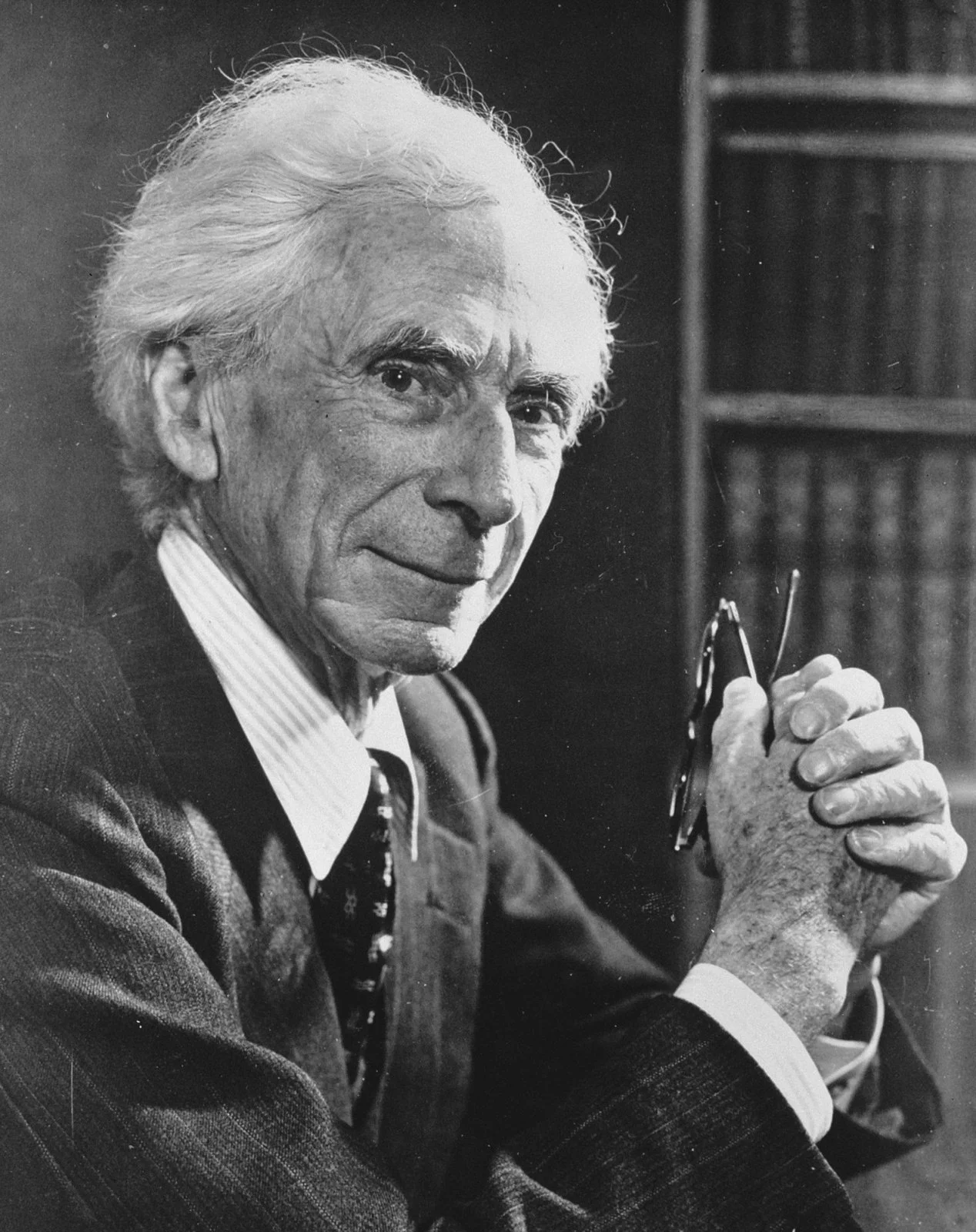

Bertrand Russell, one of the founders of analytic philosophy, famously illustrated the problem of induction with a story about a turkey.

The story goes like this: A turkey is fed by a farmer every single morning. Being a smart turkey who applies Bayesian statistics (using new information to constantly update probabilities), he updates his belief system every day.

Day 1: Farmer brings food. The farmer is my friend.

Day 100: Farmer brings food. The farmer is definitely my friend.

Day 364: Farmer brings food. My certainty of the farmer's love is at an all-time high.

Then Christmas arrives, and the farmer beheads him.

The turkey’s expectation of safety was blown apart because he assumed the future would behave like the past. He mistook a sequence of events for a guarantee of safety.

The Turkey Problem in Relationships

When I read this, I didn't think about poultry; I thought about people. The "Turkey Problem" is a perfect metaphor for betrayal in friendships and romantic relationships.

We build trust the same way the turkey does. Every time a friend shows up for us, or a partner treats us kindly, we update our internal probability: "This person loves me. This person is safe." We put our trust in them because the data tells us to.

When betrayal happens, it destroys us not just because of the act itself, but because it defies all our collected data. We feel the shock of the turkey on Christmas morning. We did the math, and the math was wrong.

The "Frequentist" Lover?

This led me to a deeper question: What if we changed our statistical method?

The turkey was a Bayesian, he let his confidence grow with every meal. But what if the turkey was a Frequentist? The frequentist method uses data from the current trial to assign probability, rather than constantly updating a prior belief based on history.

If we approached relationships this way, our certainty of a person's love wouldn't necessarily increase just because they were nice to us yesterday. We would look at every day as an isolated event.

Would this change the outcome?

If we didn't let our trust accumulate, perhaps the betrayal wouldn't sting as much. We wouldn't be "blind-sided" because we never allowed ourselves to be fully "certain." But on the flip side, can you truly have a deep relationship without that accumulation of trust?

The Turkey Problem teaches us that existence is probabilistic, not certain. We crave the deduction of "forever," but we live in the uncertainty of "for now." perhaps the pain of the turkey is simply the price we pay for the joy of trusting the farmer.